Become ALBANIAN

SPEAK LIKE A REAL NATIVE

DIVE INTO A LIFESTYLE

From its declaration of independence in 1912 to its remarkable resilience through centuries of foreign domination, Albania stands as a symbol of perseverance in European history. Its rich cultural heritage reflects influences from Illyrian, Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman, and Venetian rule, seamlessly blended with deeply rooted Albanian traditions. With its breathtaking natural beauty, from the Albanian Alps to the pristine beaches of the Ionian Sea, Albania offers an unforgettable journey through its dynamic and enduring legacy.

After the fall of communism in 1991, Albania embarked on a path of transformation, embracing democracy and economic reform. The nation has since become a thriving part of Southeast Europe, joining NATO in 2009 and actively pursuing European Union membership. Its vibrant arts scene, growing tourism sector, and emphasis on cultural preservation highlight a country that treasures its past while building a progressive future.

We have created a selection of words that you won't find in any textbook or course to make you become a real native by helping you understand Albanian words that carry a deeper cultural meaning.

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are serious about learning Albanian, we recommend that you download the Complete Albanian Master Course.

You will receive all the information available on the website in a convenient portable digital format as well as additional contents: over 15.000 Vocabulary Words and Useful Phrases, in-depth explanations and exercises for all Grammar Rules, exclusive articles with Cultural Insights that you won't find in any other textbook so you can amaze your Albanian friends or business partners thanks to your knowledge of their country and history.

With a one-time purchase you will also get hours of Podcasts to Practice your Albanian listening skills as well as Dialogues with Exercises to achieve your own Master Certificate.

Start speaking Albanian today!

AHMET ZOGU

Ahmet Zogu (1895–1961) was one of the most influential and controversial figures in modern Albanian history. He served as kryeministër (prime minister), president, and eventually mbret i shqiptarëve (King of the Albanians), transforming himself from a regional chieftain into a self-declared monarch. His political career shaped Albania during a critical period of state formation and modernization between the two world wars.

Born in Burgajet, near Mat, to a powerful feudal family, Ahmet Zogu emerged as a national leader after Albania's independence from the Ottoman Empire. He gained influence in the turbulent early years of Albanian statehood and, by the early 1920s, had become ministri i Brendshëm (Minister of the Interior) and later kryeministër (Prime Minister). Known for his political ambition and shrewdness, Zogu navigated internal revolts, tribal rivalries, and regional power struggles.

In 1924, a democratic uprising led by Fan Noli overthrew Zogu and established a short-lived reformist government. Zogu fled to Jugosllavi (Yugoslavia), but returned just six months later with foreign support, reclaimed power, and soon declared himself President of the Republic in 1925. Three years later, in 1928, he proclaimed the Monarkia Shqiptare (Albanian Kingdom) and crowned himself Mbret Zog I (King Zog I), becoming the only European Muslim monarch of the 20th century.

As king, Zog sought to modernize Albania’s institutions, legal system, and economy. He introduced a new kushtetutë (constitution), promoted arsimimi laik (secular education), and attempted to centralize authority by curbing the power of tribal leaders and the traditional kanun (customary law). He also worked to reduce the influence of religious institutions in governance. However, his reign was marked by autoritarizëm (authoritarianism), heavy censorship, and a reliance on foreign loans—particularly from Italia fashiste (Fascist Italy).

Despite initial attempts to maintain independence, Albania increasingly fell under Italy’s influence. In 1939, just before the outbreak of World War II, Mussolini’s forces invaded Albania. King Zog fled into exile with his wife Geraldine and newborn son Leka, refusing to abdicate but losing all political power. He spent the rest of his life in exile, primarily in Egypt and later France, where he died in 1961.

Zogu's legacy remains complex. Some view him as a nation-builder who gave Albania political structure, national identity, and international recognition. Others criticize his regjim personalist (personalist regime), his failure to resist foreign domination, and his self-coronation. Nevertheless, Ahmet Zogu stands as a pivotal figure in the history of 20th-century Albania—ambitious, resilient, and central to the formation of the modern Albanian state.

BEKTASHI

Bektashi is a tarikat mysliman (Muslim Sufi order) that has played a deeply influential role in Albanian religious, cultural, and national identity, especially among myslimanët shqiptarë (Albanian Muslims). Known for its mistike liberale dhe tolerante (liberal and tolerant mysticism), the Bektashi Order is unique in the Islamic world and has long been associated with values of dashuri, paqe, barazi, and vëllazëri universale (love, peace, equality, and universal brotherhood).

The Bektashi order was founded in the 13th century in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) by Haxhi Bektash Veli, a mystic and spiritual figure who promoted Sufizmi (Sufism)—a form of Islamic spirituality focused on inner purification and union with the divine. Bektashism later spread throughout the Perandoria Osmane (Ottoman Empire), gaining particular popularity among jançarët (the Janissary corps), who were deeply connected to the order until the corps was dissolved in the 19th century.

In Albania, Bektashism took strong root, especially in juglindje e vendit (the country’s southeast), in regions like Skrapar, Tepelenë, Korçë, and Elbasan, and among Albanians in Kosovo and North Macedonia. After the suppression of Sufi orders in Turkey in 1925, the Bektashi world headquarters (Kryegjyshata Botërore Bektashiane) was moved to Tiranë, where it remains today.

What makes Bektashizmi shqiptar (Albanian Bektashism) distinct is its fusion of besim fetar (religious faith) with identitet kombëtar shqiptar (Albanian national identity). Bektashis were active supporters of the Rilindja Kombëtare (National Awakening), and many key figures in Albania’s independence movement—such as Naim Frashëri—were Bektashis. Their teachings emphasize arsimi, harmonia fetare, and liria e ndërgjegjes (education, interfaith harmony, and freedom of conscience), and they have often served as a bridge between religious and secular Albanian values.

Bektashism differs from mainstream Sunni Islam in several ways. It venerates Aliu (Imam Ali), values hierarkia shpirtërore (spiritual hierarchy), and incorporates elements of rituale ezoterike, meditim, and simbolikë e thellë (esoteric rituals, meditation, and deep symbolism). Its rituals often involve gatherings at teqe (Bektashi lodges), participation in shared meals (agape), and the celebration of sacred days like Sulltan Nevruzi (March 22), which marks both the new spiritual year and the birth of Imam Ali.

During the communist era, when feja u ndalua në Shqipëri (religion was banned in Albania), Bektashi institutions were severely repressed, and many teqe were destroyed or closed. Since the 1990s, however, there has been a rilindje shpirtërore (spiritual revival) of Bektashism in Albania, with the reconstruction of teqes, a renewed public presence, and increased interest in the order’s message of peace and unity.

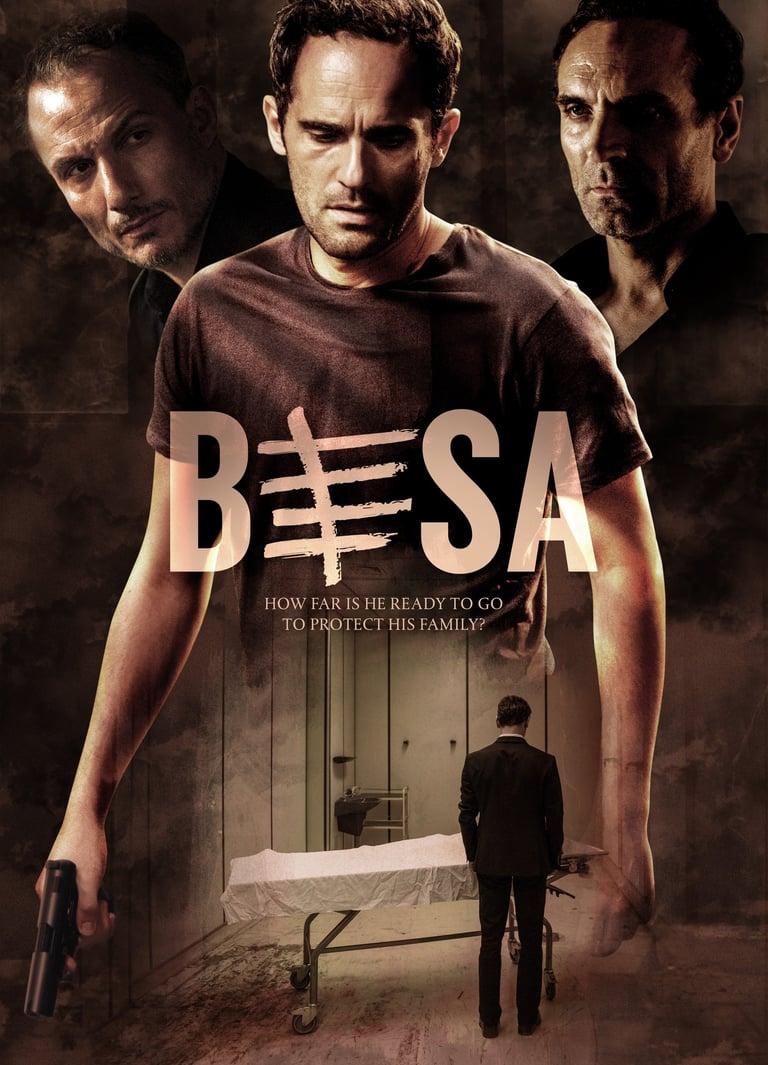

BESA

Besa is one of the most powerful and defining concepts in Albanian culture, representing a solemn promise, a word of honor, and a deep moral obligation that transcends legal or written contracts. Rooted in the traditional Kanun (code of law), particularly the Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit (Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini), besa is more than just a personal pledge—it is a sacred trust that must not be broken. When an Albanian gives their besa, they are committing to act with integrity, protect others, and uphold their word no matter the circumstances.

Historically, besa has played a crucial role in regulating social relations in regions where formal institutions were weak or absent. It served as a guarantee of safety and trust in both private and public affairs. For instance, during blood feuds or gjakmarrje (blood revenge), the giving of besa could temporarily suspend hostilities, allowing families to move freely and attend important events like funerals or weddings without fear of retaliation. This act of giving a besa e përkohshme (temporary truce) was considered sacred and universally respected, even among enemies.

One of the most extraordinary examples of besa in practice occurred during World War II, when thousands of Albanian families risked their lives to shelter and protect Jewish refugees. In accordance with the unwritten law of mikpritja (hospitality), many Albanians believed that offering protection to those in danger was a moral duty, especially once they had given their besa. In these cases, the honor of keeping one’s word outweighed any fear of punishment or death. To this day, Albania is one of the few countries in Europe where the number of Jews increased during the Holocaust.

Besa is closely tied to other traditional values like nderi (honor), besnikëria (loyalty), and trimëria (bravery), all of which are fundamental to Albanian identity. It is often taught from a young age within families and reinforced through storytelling, proverbs, and daily life. Phrases like “besa është më e shenjtë se jeta” (honor is more sacred than life) reflect the depth of this cultural norm.

Even in modern Albania, where formal legal systems have replaced much of the traditional Kanun, the notion of besa still carries great weight. It is not uncommon for someone to say “të jap besën” (I give you my word) when making a serious promise. As a living tradition, besa continues to shape how Albanians view trust, responsibility, and the moral fabric of society.

BUNKERË

Bunkerë (bunkers) are one of the most iconic and unusual features of the Albanian landscape, representing a powerful and often paradoxical symbol of paranoia, isolation, and national identity during the communist era. These small, dome-shaped concrete structures—known in Albanian as bunkerë betoni (concrete bunkers)—were built under the regime of Enver Hoxha, who ruled Albania with an iron fist from 1944 to 1985.

Between the 1960s and 1980s, the Albanian communist government constructed an estimated 170,000 to 750,000 bunkers throughout the country. They were meant to protect the population from an invasion that never came. The regime, deeply mistrustful of both NATO and the Warsaw Pact, adopted a doctrine of mbrojtje totale (total defense), preparing every citizen to become a soldier if necessary.

The bunkers vary in size—from small bunkerë për një ushtar (one-man bunkers) to larger postbunkerë (command posts) and sisteme të tëra nëntokësore (entire underground systems). They were placed in fshatra, qytete, male, plazhe, and even along rrugë të zakonshme (villages, cities, mountains, beaches, and roads), making them omnipresent in Albanian life. Many were built using çimento e përforcuar (reinforced concrete) and tested under extreme conditions—including live artillery fire.

Though originally intended for defense, the bunkerë were never used for their military purpose. After the fall of communism in the early 1990s, they were left abandoned, becoming silent relics of a closed and heavily militarized past. Over time, public attitudes toward them evolved—from symbols of fear and oppression to objects of curiosity, memory, and even ironike (irony).

In recent years, Albanians have repurposed some bunkerë creatively: turning them into kafene, muze, strehimore, or even shtëpi pushimi (cafés, museums, shelters, or vacation homes). In Tiranë, the capital, two former underground military sites—Bunk’Art 1 and Bunk’Art 2—have been transformed into powerful muze historikë dhe artistikë (historical and artistic museums), documenting the country's totalitarian past and promoting dialogue about memory, trauma, and identity.

BYREK

Byrek is one of the most beloved and widely consumed dishes in Albanian cuisine, known for its flaky texture, savory fillings, and comforting flavor. Found in nearly every bakery and household across the country, byrek consists of thin layers of petë (phyllo dough) filled with various ingredients, then baked until golden and crispy. It is enjoyed at any time of day—whether as a quick breakfast, light lunch, or part of a family meal. The most common fillings include djathë i bardhë (white cheese), spinaq (spinach), mish i grirë (minced meat), and kungull (zucchini), though regional and seasonal variations abound.

In northern Albania, you might encounter byrek me lakra (cabbage byrek), while in the south, byrek me qepë e domate (onion and tomato byrek) is a summer favorite. In the countryside, many families still prepare byrek from scratch using homemade petë, which are stretched and rolled by hand—a skill passed down through generations. This process often takes place in the sahan (wide tray), and the final product is baked in a traditional furrë druri (wood-fired oven), giving the dish a rustic, smoky flavor.

A well-made byrek is prized not just for its taste but also for its texture. Each layer of dough should be thin and delicate, with a crisp outer shell and soft interior where the filling blends harmoniously with the pastry. The layering process requires patience and practice, especially when making byrek me dorë (handmade byrek), a version where the dough is not store-bought but kneaded, stretched, and shaped entirely by hand. In some homes, byrek me vezë e qumësht (byrek with eggs and milk) is poured over the top before baking to create a richer and more custard-like result.

Byrek is also central to Albanian hospitality. When guests arrive, it is common to offer a warm slice of byrek, often accompanied by kos (yogurt) or dhallë (buttermilk). During picnics, school lunches, or road trips, byrek wrapped in paper is a reliable and satisfying snack. On festive occasions, larger trays are prepared and shared among extended family and neighbors, reinforcing the values of mikpritja (hospitality) and bashkëndarja (sharing).

DITA E VERËS

Dita e Verës (Summer Day) is one of the most ancient and beloved traditional festivals in Albania, celebrated every year on March 14 (according to the old Julian calendar) as a symbol of spring's arrival, renewal, and light overcoming darkness. Rooted in pagan Illyrian rituals and seasonal cycles, the holiday is especially popular in Elbasan, where it has become the heart of the celebration, though it is recognized throughout the country and among the diaspora shqiptare (Albanian diaspora).

Originally a celebration of the zoti i natyrës dhe i pjellorisë (god of nature and fertility), Dita e Verës marks the end of dimri (winter) and the beginning of verës (summer), symbolizing rilindja e natyrës (nature's rebirth) and freskia e jetës së re (freshness of new life). It is a time when people express hope for health, happiness, and prosperity.

One of the most recognizable features of Dita e Verës is the ballokume—a traditional ëmbëlsirë prej misri (corn flour cookie) originally from Elbasan, made with miell misri, gjalpë, sheqer, and vezë (cornmeal, butter, sugar, and eggs). Preparing and sharing ballokume is a central part of the day, and many households in Elbasan proudly follow receta familjare (family recipes) passed down through generations.

People also celebrate by going outside, shëtitje në natyrë (walking in nature), gathering with family and friends, and lighting zjarre simbolike (symbolic fires), which are meant to largojnë të keqen (ward off evil) and pastrojnë shpirtin dhe trupin (cleanse the soul and body). Young people often kërcëjnë mbi zjarrin (jump over the fire) as a playful ritual of pastrim dhe guxim (cleansing and courage).

Children and young adults wear verore—colorful byzylykë të punuar me fije të kuqe dhe të bardha (bracelets made with red and white thread), which symbolize fat i mirë (good luck) and are often tied to trees or burned at the end of the day. These small gestures reflect ancient beliefs in cikli i natyrës (the cycle of nature) and ndikimi i natyrës në jetën njerëzore (nature’s influence on human life).

In modern times, Dita e Verës has taken on a more festive, civic spirit. In Tiranë and especially Elbasan, the streets fill with music, folk dancing, artisan fairs, and street food, turning the day into a public celebration of trashëgimi kulturore (cultural heritage) and optimizëm kombëtar (national optimism).

EDI RAMA

Edi Rama is the current Kryeministër i Shqipërisë (Prime Minister of Albania), a prominent political figure, artist, and former mayor of Tirana who has played a major role in shaping modern Albanian politics. Born in Tiranë in 1964, Rama entered public life first as a piktor (painter) and profesor i arteve (art professor) before transitioning into politics in the late 1990s.

He gained public attention not only for his outspoken nature but also for his distinctive personal style, often wearing unconventional suits and sneakers, and for blending arti me politikën (art with politics). Edi Rama is the son of Kristaq Rama, a well-known sculptor and member of the former communist elite, but Edi carved a path of his own after the fall of communism.

His political career began after he served briefly as Ministër i Kulturës (Minister of Culture) from 1998 to 2000, where he was known for promoting contemporary art and cultural reform. He then ran for mayor of Tirana, winning the office in 2000. As Kryetar i Bashkisë së Tiranës (Mayor of Tirana), Rama became famous for his campaign to paint grey communist-era buildings in bright colors, launch urban clean-up projects, and promote green spaces—earning both praise and criticism. He held this position for over a decade, transforming Tirana’s image and increasing his national popularity.

In 2005, Rama became the leader of the Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (Socialist Party of Albania), the main center-left political force in the country. After years in opposition, he led his party to victory in the 2013 elections and became Prime Minister, succeeding Sali Berisha.

As Prime Minister, Edi Rama has focused on reforma në drejtësi (judicial reform), modernizimi i infrastrukturës (infrastructure modernization), arsim dhe shëndetësi publike (education and public healthcare), and pursuing integrimi evropian (European integration). His government has overseen the opening of EU accession negotiations, though progress has been slow and fraught with criticism over corruption, lack of transparency, and media freedom concerns.

Rama has been re-elected twice, in 2017 and 2021, making him the longest-serving head of government in post-communist Albania. His leadership style is often described as qendralist (centralized), karizmatik, and at times polarizues (polarizing), as he maintains a strong presence in both domestic and international media.

KANUN

Kanun is the traditional Albanian code of law, a comprehensive set of customary rules that governed social behavior, justice, and moral obligations in Albanian communities for centuries. Rooted in oral tradition, the Kanun was most famously codified in the 15th century by Lekë Dukagjini, a nobleman from northern Albania, and thus is often referred to as the Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit (Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini). It was not written down until the early 20th century, yet it remained the foundation of social order in many krahinat malore (mountain regions), particularly in the north.

The Kanun covers a wide range of topics, including nderi (honor), besa (word of honor), gjakmarrja (blood feud), mikpritja (hospitality), familja (family), pronësia (property), and trashëgimia (inheritance). It was enforced by the local community, particularly by pleqtë e fshatit (village elders), who were seen as the guardians of tradition and fairness. Although it was not backed by a formal judicial system, its rules were deeply respected and strictly followed, with shkelja e Kanunit (violating the Kanun) often leading to social exclusion or retaliatory action.

One of the most well-known and controversial aspects of the Kanun is gjakmarrja, the blood feud system, which permitted a family to seek revenge if one of its male members was killed. This cycle of violence could continue for generations unless a besa (truce) was granted. While gjakmarrja is often emphasized in discussions of the Kanun, the code itself is much broader and includes detailed instructions on conflict resolution, contracts, marriage arrangements, and the protection of guests. The value of mikpritja (hospitality) is particularly sacred: a guest under one’s roof was to be protected at all costs, even at the risk of one's own life.

Despite its origins in a patriarchal and tribal society, the Kanun reflects a sophisticated legal structure based on mutual respect and community cohesion. During the communist era, the practice of the Kanun was officially suppressed, but it remained active in remote areas. In the post-communist period, particularly during times of weak state authority in the 1990s, it re-emerged, sometimes in distorted forms that departed from its traditional spirit.

KËNGËT POLIFONIKE

Këngët polifonike (polyphonic songs) are a deeply rooted and unique form of Albanian traditional music, characterized by the simultaneous singing of multiple independent vocal lines. This style is especially prominent in southern Albania, particularly in the regions of Labëria, Toskëria, and Çamëria, and is considered one of the most distinctive expressions of kultura gojore shqiptare (Albanian oral culture).

Albanian polyphonic singing is traditionally performed a cappella, with no instruments, and involves two to four main roles:

– Marrësi (the taker) – the lead singer who begins the song and carries the main melodic line

– Kthyesi (the returner) – who responds to or overlaps with the lead

– Hedhësi (the thrower) – who adds emotional or melodic tension (common in Labëria)

– Isoja (the drone) – the group that sustains a continuous, humming tone, creating a vocal base

This layered texture produces a rich and haunting harmoni vokale (vocal harmony), often using intervale të pazakonta (unusual intervals) and intonacione arkaike (archaic intonations) that set it apart from Western polyphony. The iso part, in particular, creates a drone-like background that gives the song its deep resonance and spiritual intensity.

Këngët polifonike are performed in various contexts:

– During festat familjare (family celebrations) such as weddings or funerals

– At ngjarje shoqërore (community gatherings) and feste lokale (local festivals)

– As a form of kthim kujtese (commemoration) for ancestors or historical events

Themes in these songs include dashuria (love), trimëria (heroism), mërgimi (exile), vdekja (death), and historia (history), often drawing from kujtesa kolektive (collective memory) and passed down gojë më gojë (orally from generation to generation).

In 2005, këngët polifonike të Shqipërisë (the polyphonic songs of Albania) were recognized by UNESCO as part of the "Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity", a testament to their cultural and artistic value.

The most well-known style is the polifonia labe, sung by men in Labëria, marked by deep emotional expression and the presence of hedhësi, which adds dramatic flair. However, Toske and Çame variations, including female polyphony, are equally rich and important.

Today, efforts are being made to preserve këngët polifonike through grupe folklorike (folk groups), festivale si Gjirokastra (festivals like the one in Gjirokastër), and recordings that document these intricate vocal traditions.

NËNË TEREZA

Nënë Tereza (Mother Teresa), born as Gonxhe Bojaxhiu in Shkup (Skopje) in 1910 to an Albanian family, is one of the most revered humanitarian figures of the 20th century. Though she lived much of her life abroad, Albanians across the world consider her a symbol of mëshirë, dashuri, and shërbim ndaj njerëzimit (mercy, love, and service to humanity). She is often referred to as Shenjtorja e shqiptarëve (the saint of the Albanians).

From a young age, Gonxhe felt called to a life of religious service. At 18, she left home to join the Urdhri i Loretos (Order of the Loreto Sisters) in Ireland, where she received the name Sister Teresa. Shortly after, she was sent to India, where she would spend the rest of her life. In 1950, she founded the Misionaret e Dashurisë (Missionaries of Charity), an order devoted to serving “the poorest of the poor” in the slums of Kalkuta (Calcutta).

Nënë Tereza became a global icon for her work among the sick, orphaned, and dying. Her mission extended far beyond India—she opened homes, hospices, and charity centers around the world, including in Tiranë, Shkodër, and Durrës, after the fall of communism in Albania. She visited Albania in 1989, soon after religious freedoms were restored, and received a hero’s welcome.

She was awarded numerous honors during her lifetime, including the Çmimi Nobel për Paqen (Nobel Peace Prize) in 1979. Despite facing criticism from some circles regarding her methods and religious beliefs, her personal dedication, simplicity, and tireless service to those in need earned her immense global respect.

After her death in 1997, Nënë Tereza was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 2003 and canonized as Shenjtorja Tereza e Kalkutës (Saint Teresa of Calcutta) by Pope Francis in 2016. Today, her legacy lives on not only through the Missionaries of Charity but also through her lasting message of dashuri pa kushte (unconditional love), besim i thellë (deep faith), and shërbim për më të varfërit (service to the poorest).

In Albania, her image is celebrated in schools, churches, and public life. Aeroporti Ndërkombëtar i Tiranës (Tirana International Airport) bears her name, and a large statue stands in central Tirana

RAKI

Raki is a traditional Albanian pije alkoolike (alcoholic drink), most commonly distilled from rrush (grapes), though other fruits like fiku (figs), mani (mulberries), or dardha (pears) are also used in some regions. Strong, clear, and deeply aromatic, raki holds a central place in kultura shqiptare (Albanian culture), not only as a beverage but as a symbol of hospitality, celebration, and community.

The most common type is raki rrushi (grape raki), made after the grape harvest in early autumn. After the shtrydhja e rrushit (grape pressing) for wine, the leftover skins, seeds, and pulp—called tulina—are collected and fermented. The fermented mixture is then distilled using a kazan (copper still), often in the courtyards or oborre of homes in the countryside. This process is usually a family or community affair, where generations gather to take part, tell stories, and share food while watching over the slow, careful distillation.

Homemade raki is typically strong, often ranging from 40% to 50% alcohol by volume, though some can be even stronger. It’s clear in color, served in small glasses, and enjoyed at all hours of the day—në mëngjes me kafe (in the morning with coffee), para drekës (before lunch), or gjatë darkave festive (during festive dinners). In rural areas, a glass of raki is the first thing offered to a guest, reflecting the Albanian value of mikpritja (hospitality).

Beyond its role as a social drink, raki is also used for medicinal purposes. Many believe it helps with ftohje (colds), dhimbje barku (stomach aches), or even as a disinfectant for wounds. Raki me mjaltë dhe limon (raki with honey and lemon) is a common home remedy for sore throats, served warm like a soothing elixir.

Different regions of Albania take pride in their own styles of raki. For example, Skrapar, Berat, and Përmet are famous for producing high-quality, smooth-tasting raki rrushi, while raki mani from the south is especially fragrant and slightly sweeter. In some areas, raki is aged in wooden barrels, giving it a light golden color and a more refined flavor.

SKANDALI PIRAMIDAL

Skandali piramidal (the pyramid scheme scandal) refers to one of the darkest and most destabilizing periods in post-communist Albanian history. Taking place primarily in 1996–1997, the scandal involved a series of fraudulent investment schemes—known as firmat piramidale (pyramid firms)—that promised massive returns and ultimately led to the financial ruin of hundreds of thousands of Albanians, widespread civil unrest, and near collapse of the state.

After the fall of communism in the early 1990s, Albania transitioned rapidly to a free-market economy, but without the proper infrastrukturë ligjore dhe financiare (legal and financial infrastructure). In this environment of uncertainty and mungesë e kontrollit shtetëror (lack of state oversight), several companies emerged offering seemingly legitimate investment opportunities. These firms—such as VEFA, Gjallica, and Populli—promised high interest rates (up to 100% or more in a few months), luring in ordinary citizens who deposited their life savings, pensions, and even sold property or livestock to invest.

Unregulated and operating much like classic skema Ponzi (Ponzi schemes), these companies used new investors’ money to pay earlier ones, creating the illusion of profitability. As trust in the banking system was still low, many Albanians believed these firms were supported by the government, especially since officials often ignored warnings and even appeared to endorse or protect them.

By early 1997, the pyramid schemes began to collapse. When investors attempted to withdraw their money, the firms could no longer sustain payments. The total loss was estimated at 1.2 billion USD, which, at the time, equaled nearly half of Albania’s GDP. As families lost everything, zemërimi popullor (public anger) erupted into massive protests, looting, and eventually dhunë civile (civil violence). Government authority disintegrated in many parts of the country, especially in the south.

In March 1997, President Sali Berisha declared a state of emergency, but the unrest only deepened. Weapons were looted from military depots, and armed groups took control of cities like Vlorë, Sarandë, and Gjirokastër. The country was on the brink of luftë civile (civil war). Dozens died in the chaos, and thousands attempted to flee abroad. To prevent total collapse, the international community intervened with Operacioni Alba, a multinational peacekeeping mission led by Italy.

The skandali piramidal had long-term consequences: the fall of the Berisha government, economic devastation, loss of public trust, and a mass migration wave. It remains a powerful example of how mashtrimi financiar (financial fraud), when combined with weak institutions and poor governance, can devastate an entire nation.

SKËNDERBEU

Skënderbeu (Skanderbeg), born Gjergj Kastrioti around 1405, is Albania’s national hero and one of the most celebrated figures in the country’s history. He is remembered for his fierce resistance against the Perandoria Osmane (Ottoman Empire) during the 15th century and for uniting Albanian principalities under one cause—mbrojtja e atdheut (defense of the homeland).

Gjergj Kastrioti was born into the noble familja Kastrioti, a powerful Albanian feudal family. As a child, he was taken by the Ottomans as a political hostage and raised in the imperial court, where he was converted to Islam and trained as a soldier. Renamed İskender Bey (Skanderbeg), after Alexander the Great, he rose to the rank of general in the Ottoman army. However, in 1443, during a campaign in Hungary, he defected from the Ottomans and returned to Albania, reclaiming his family’s fortress in Krujë.

Upon his return, Skënderbeu renounced Islam and declared Christian allegiance, rallying the Albanian nobility to form a unified resistance known as the Lidhja e Lezhës (League of Lezhë) in 1444. For the next 25 years, he led a successful guerrilla campaign against the Ottoman Empire, defending Albanian territories with remarkable strategic skill and limited resources. His greatest military achievement was holding the fortress of Krujë through multiple sieges, despite overwhelming Ottoman forces.

Skënderbeu’s resistance made him a symbol of liri (freedom), besë (honor), and bashkim kombëtar (national unity). He earned admiration across Europe, especially from the Papacy, Naples, and Venice, which saw him as a key Christian bulwark against Ottoman expansion into the West. Though he died in 1468 in Lezhë, his legacy lived on, inspiring future generations of Albanians in their fight for independence.

Today, Skënderbeu is honored as a central figure in Albanian identity. His equestrian statue stands proudly in Sheshi Skënderbej (Skanderbeg Square) in Tirana, and his name is found on streets, institutions, and schools across the Albanian-speaking world. The double-headed eagle on the Albanian flag is a symbol closely associated with him, reinforcing his image as a protector of the nation.

VIRGJËRSHAT E BETUESHME

Sworn virgins—known in Albanian as "virgjëresha të betuara"—are women who, in accordance with traditional Albanian Kanun (customary law), take a lifelong vow of celibacy and live publicly as men, both in dress and social role. This centuries-old practice, primarily found in northern Albania, Kosovo, and parts of Montenegro, reflects the intersection of gender, honor, and family structure in traditional Albanian society.

The practice originated in patriarchal tribal communities governed by the Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit, where only men could inherit property, lead households, or represent families in public and legal matters. If a family lacked male heirs—or in cases where a man was killed in a gjakmarrje (blood feud)—a daughter could assume the male role to protect family honor and continuity.

To become a sworn virgin, a woman would take a public oath of virgjëri e përjetshme (lifelong virginity) in front of village elders or family members. After this declaration, she would adopt a male name, wear veshje burrash (men’s clothing), cut her hair short, and perform the social and economic duties traditionally reserved for men—such as managing land, carrying weapons, smoking, drinking raki, or participating in council meetings.

Despite being biologically female, a virgjëreshë e betuar was considered "honorary male" and received full social status as a man. She was referred to with masculine pronouns and granted respect and privileges denied to women under the Kanun. This transformation was not based on gender identity in the modern sense but rather on nevojë shoqërore (social necessity) and ndeshmëri (honor).

Importantly, becoming a sworn virgin was not always a burden; for some, it provided autonomi personale (personal autonomy) in a rigidly gendered world. Women who wanted to avoid arranged marriages or pursue roles outside traditional female expectations could do so under this role, though at the cost of renouncing sexual and romantic relationships.

Today, the practice of sworn virgins has nearly disappeared, with only a few aging individuals still alive—mostly in remote areas of Malësia e Madhe, Shkodra, or northern Kosovo.

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are serious about learning Albanian, we recommend that you download the Complete Albanian Master Course.

You will receive all the information available on the website in a convenient portable digital format as well as additional contents: over 15.000 Vocabulary Words and Useful Phrases, in-depth explanations and exercises for all Grammar Rules, exclusive articles with Cultural Insights that you won't find in any other textbook so you can amaze your Albanian friends or business partners thanks to your knowledge of their country and history.

With a one-time purchase you will also get hours of Podcasts to Practice your Albanian listening skills as well as Dialogues with Exercises to achieve your own Master Certificate.

Start speaking Albanian today!